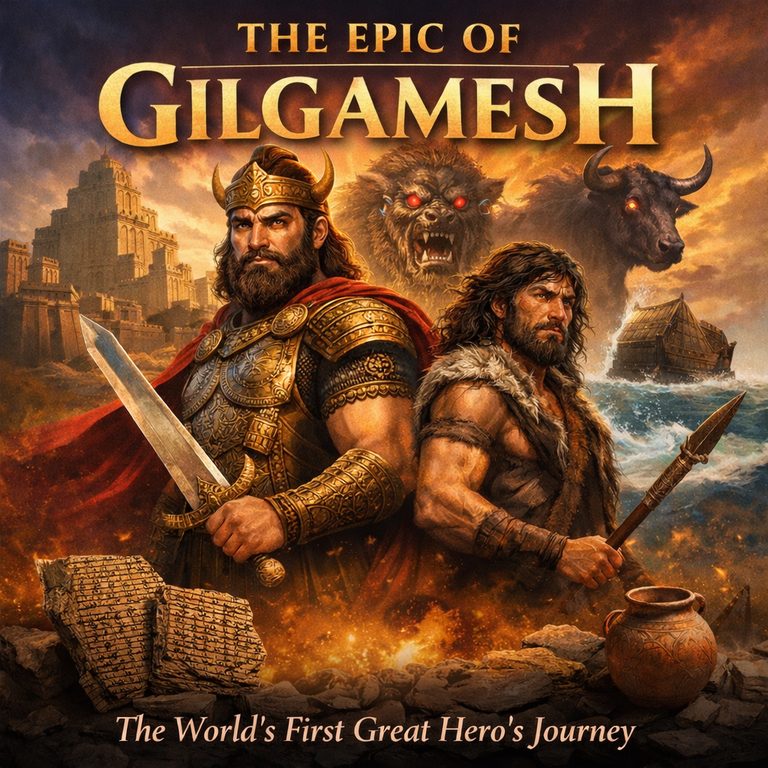

A Timeless Story of Kingship, Friendship, and the Search for Immortality

The Epic of Gilgamesh is widely regarded as the oldest surviving work of great literature in human history. Originating in ancient Mesopotamia over 4,000 years ago, this powerful narrative predates Homer’s epics and even many Biblical accounts. Inscribed on clay tablets in cuneiform script, the story was rediscovered in the 19th century among the ruins of the ancient library of Ashurbanipal in Nineveh.

At its heart, the epic is a profound meditation on power, mortality, friendship, and the limits of human ambition.

The Tyrant King of Uruk

The story begins in the great city of Uruk, ruled by the mighty king Gilgamesh. Two-thirds divine and one-third human, Gilgamesh is unmatched in strength, courage, and intellect. Yet his greatness is corrupted by arrogance. He oppresses his people, abuses his authority, and acts without restraint.

The gods, hearing the cries of Uruk’s citizens, decide to create a rival to challenge him.

The Creation of Enkidu

The gods fashion Enkidu from clay — a wild, untamed man who lives among animals. After being civilized through human contact, Enkidu travels to Uruk to confront Gilgamesh.

Their clash is legendary. But rather than remaining enemies, the two recognize each other as equals. From combat is born one of literature’s first and greatest friendships.

The Quest for Glory

United by ambition, Gilgamesh and Enkidu seek immortal fame. They journey to the Cedar Forest to slay its monstrous guardian, Humbaba. Despite divine warnings, they defeat him and claim victory.

Later, the goddess Ishtar proposes marriage to Gilgamesh. He rejects her harshly, recounting her past lovers’ fates. Enraged, Ishtar sends the Bull of Heaven to punish Uruk. Once again, the two heroes prevail.

But this defiance of divine order carries consequences.

The Death of Enkidu

The gods decree that one of the heroes must die. Enkidu falls gravely ill and, after suffering deeply, dies. His death devastates Gilgamesh.

For the first time, the mighty king confronts a terrifying truth: he too must die.

Grief-stricken and afraid, Gilgamesh abandons his throne and wanders the wilderness in search of eternal life.

The Search for Immortality

Gilgamesh seeks out Utnapishtim, the only mortal granted immortality by the gods. Utnapishtim tells him of a great flood sent by the gods — a story strikingly similar to the Biblical flood narrative — and explains that immortality was a unique gift never meant to be repeated.

Still, he offers Gilgamesh a test: stay awake for six days and seven nights. Gilgamesh fails.

As a final gesture, Utnapishtim reveals the location of a plant that restores youth. Gilgamesh retrieves it, believing he has finally secured triumph over death. But while resting, a serpent steals the plant and sheds its skin — symbolizing renewal denied to humanity.

The Return to Uruk

Empty-handed, Gilgamesh returns to Uruk. Yet he is no longer the tyrant who left. He understands that immortality lies not in eternal life, but in enduring legacy — in the walls he built, the civilization he shaped, and the wisdom he gained.

The epic closes not with conquest, but with reflection.

Themes That Still Resonate Today

The Epic of Gilgamesh explores timeless themes:

The inevitability of death

The value of friendship

The limits of human power

Civilization versus nature

The meaning of legacy

It is a story that asks the same questions humanity still wrestles with today:

What does it mean to live well, knowing we must die?

Why It Still Matters

Long before the works of Homer, this Mesopotamian epic shaped the foundations of heroic storytelling. Its influence echoes through Greek myth, Biblical literature, and modern fantasy alike.

For readers, writers, historians, and philosophers, The Epic of Gilgamesh is not merely an ancient artifact — it is a mirror reflecting humanity’s oldest fears and greatest aspirations.

More than four millennia later, the voice from those clay tablets still speaks

Read the Full Story

If you enjoyed this story overview, you can read the entire epic book here rewritten in a concise modern English version: